Tantalum-based dental implants are gaining attention as a next-generation alternative to traditional titanium systems due to their strong biocompatibility, osteoconductive behavior, and potential to improve bone–implant bonding. A major advantage is tantalum’s highly porous, trabecular-like architecture, which closely resembles cancellous bone and supports bone ingrowth and vascular development. This interconnected porosity encourages cellular attachment, osteocyte migration, and stable biological fixation—key factors for long-term implant performance.

However, several limitations restrict broad clinical adoption. Tantalum is expensive, and its manufacturing often requires complex processes such as chemical vapor deposition and powder-based methods, increasing both cost and technical difficulty. In addition, long-term clinical outcomes in dentistry remain limited, and concerns about durability in the oral environment, optimization of implant geometry, and standardized protocols are still unresolved. While early studies report promising results, more high-quality clinical trials and long-term follow-ups are needed to define evidence-based indications.

This review summarizes the current landscape of tantalum implants in dentistry, explains the biological and biomechanical rationale, and highlights the major challenges that must be addressed before widespread use.

1. Introduction and Background

Dental implants have transformed rehabilitation for partial and total tooth loss, yet failure still occurs in a minority of cases (commonly reported around 5–10% in various clinical contexts). Research has increasingly focused on improving surface characteristics to strengthen bone integration and reduce complications. One emerging approach is the use of porous tantalum trabecular metal, which enhances surface topography and supports deeper biological integration.

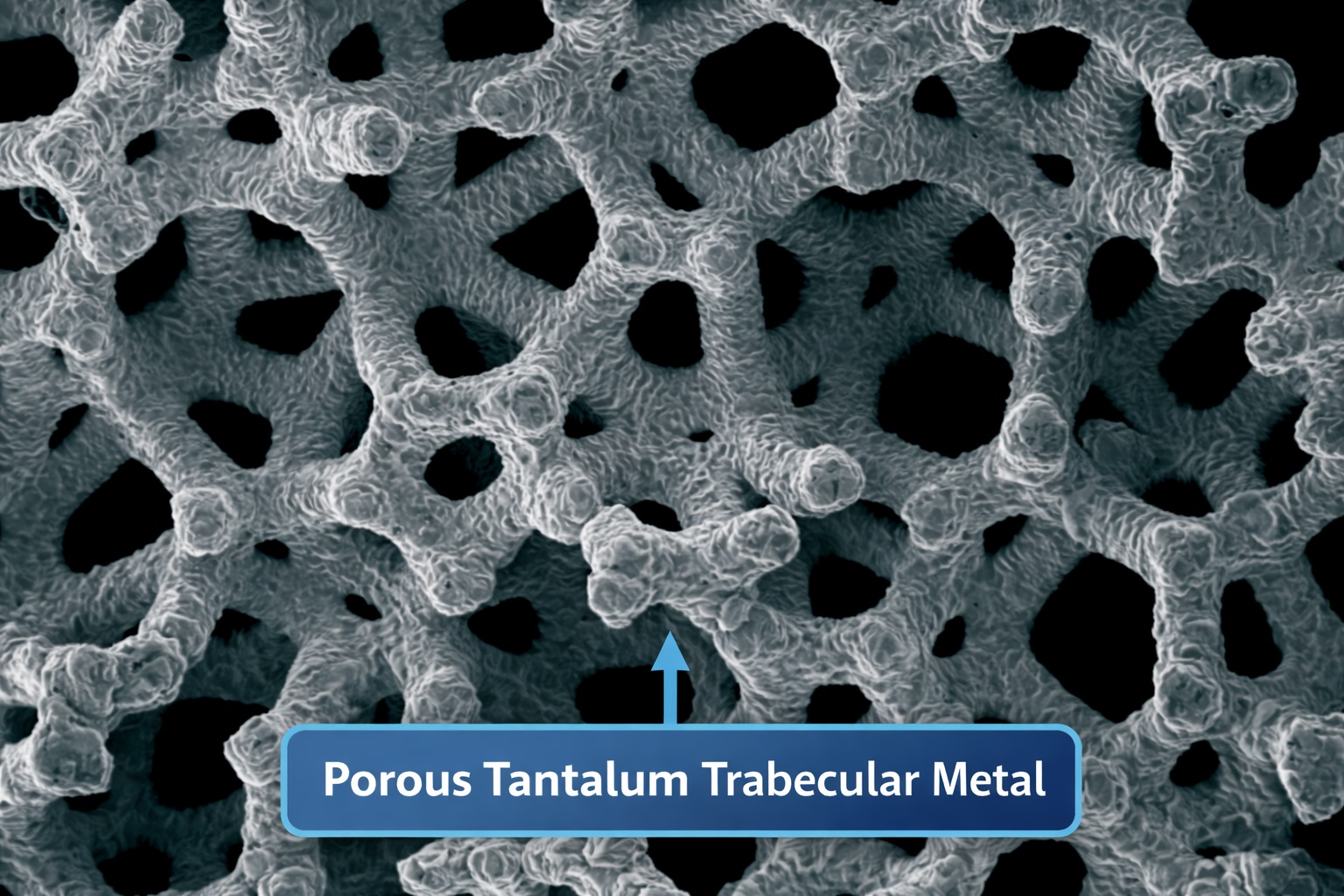

Porous tantalum trabecular metal (often referenced as PTTM) is notable for its very high porosity (around 75–80%), an architecture that imitates bone microstructure and demonstrates bone-like elastic behavior in some configurations. This design increases the effective surface area and enables not only bone growth onto the surface but also bone growth into the structure—often described as osseoincorporation.

Evidence suggests a functional difference between titanium and tantalum at the cellular level: titanium often supports strong cell proliferation, while tantalum may promote pathways linked to osteoblastic differentiation. In orthopedic settings, porous tantalum has been associated with favorable neovascularization, wound healing, and bone formation—effects that make it attractive in dental implant engineering as well.

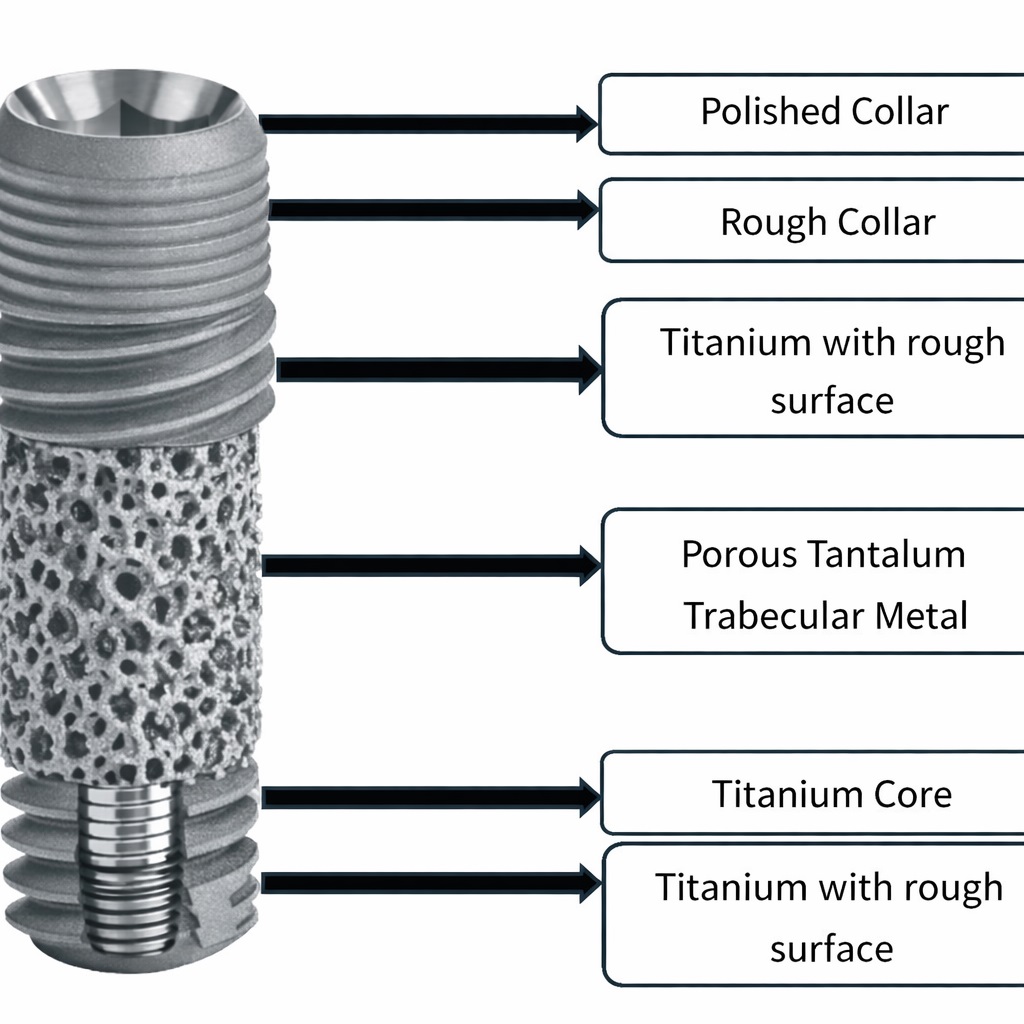

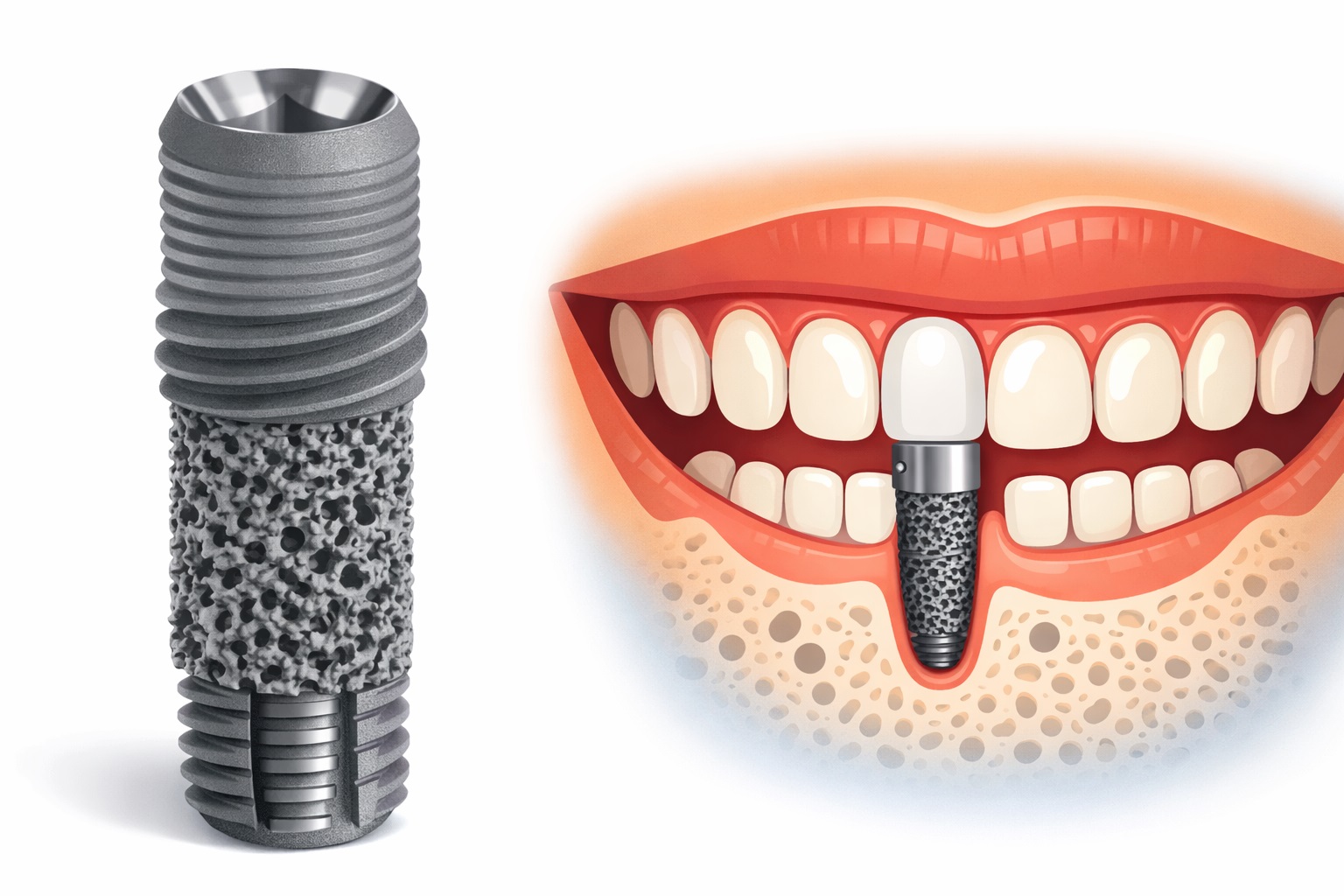

A common modern design combines both materials: a titanium alloy implant with a midsection containing porous tantalum, while the coronal and apical regions retain threaded titanium geometry. Additional surface treatments, including microtexturing and hydroxyapatite-related enhancements, may further support integration. Even with increasing research, biological events specifically occurring within the porous tantalum zone are not yet fully understood.

2. Review Method

A multi-database literature search strategy can be used to evaluate tantalum in dental implantology. Major sources typically include PubMed/Medline, Scopus, Web of Science, Embase, and the Cochrane Library, with Google Scholar supporting broader discovery. Common keyword clusters include:

- implant biomaterials

- tantalum implant

- osseoincorporation

- porous trabecular metal

- dental implant surface modification

To improve relevance, many reviews limit inclusion to peer-reviewed English publications, such as clinical trials, systematic reviews, histological studies, and case reports.

3. Historical Context of Tantalum

Tantalum (Ta), atomic number 73, is a rare transition metal known for strong corrosion resistance and chemical stability. Its name references the myth of Tantalus, reflecting the material’s historically “unreactive” behavior in many chemical environments. Tantalum was identified in the early 1800s, and later work clarified its relationship to mineral sources historically associated with columbite/tantalite. Over time, tantalum became valued as an alloying element due to its high melting point and durability.

4. Porous Tantalum Trabecular Metal (PTTM)

Although tantalum is highly biocompatible and corrosion-resistant, early medical use was limited because machining and processing solid tantalum is challenging. Traditional implant strategies relied on solid metals (like titanium) or porous ceramics (like hydroxyapatite or tricalcium phosphate), often as coatings. These approaches could not fully reproduce cancellous bone architecture and sometimes had mechanical limitations such as cracking, delamination, or weaker ductility.

The introduction of open-cell porous tantalum structures in the 1990s helped overcome these barriers by providing a bone-like internal network. This material is often described as a three-dimensional trabecular architecture made of repeating structural units. Manufacturing commonly involves creating a scaffold (often carbon-based) and depositing tantalum using a chemical vapor process, producing an interconnected porous metal framework.

This architecture can be adjusted for different clinical designs, which is one reason porous tantalum has been particularly popular in orthopedic reconstruction and revision procedures.

5. Implant Design and Manufacturing

Modern dental applications may use:

- Titanium implants enhanced with porous tantalum sections, designed to support both bone ongrowth and ingrowth.

- Titanium–tantalum alloys, including additive-manufactured lattice systems.

- Engineered porous lattice geometries (e.g., gyroid/diamond/primitive surfaces) produced through laser powder-bed fusion using blended powders.

While these engineered lattices show promise, the best structure–function combinations for dentistry (strength, fatigue behavior, peri-implant remodeling, and long-term stability) still need further validation.

6. Biological Integration Mechanisms

6.1 Osseointegration

Osseointegration refers to direct bone contact with the implant surface and the establishment of a stable bone–implant interface for load transfer and long-term fixation.

6.2 Osseoincorporation

In porous tantalum systems, bone may not only grow onto the implant but also into its porous network, with associated vascular infiltration. This deeper integration is often described as osseoincorporation, and it is considered a key differentiator from conventional surface-only integration.

6.3 Stages of Osseoincorporation (Simplified)

A typical biological sequence can be described as:

- Immediate clot formation around the implant, delivering signaling molecules.

- Inflammatory and immune response, clearing debris and initiating repair.

- Recruitment of stem cells and osteogenic precursors.

- Osteoid deposition on and within the porous network.

- Mineralization, forming mature bone.

- Remodeling, with ongoing adaptation by osteoblasts and osteoclasts.

6.4 Histologic Features

Histology often reports increased bone formation within the porous region, along with vascular channel development and signs of active remodeling. Early bone may appear woven in character before maturing over time.

7. Why Porous Tantalum May Perform Differently Than Titanium

Biological advantages

- Larger three-dimensional interface for cell attachment

- Improved pathways for vascularization within the structure

- Microenvironment that supports osteogenic activity

Biomechanical advantages

Porous architectures can help distribute forces more evenly. Some reports discuss modulus compatibility with cancellous bone in porous configurations, potentially reducing stress shielding and supporting healthier peri-implant remodeling. (Note: “elastic modulus values” vary depending on how the porous structure is measured and reported, so it’s important to present them cautiously and consistently in your final paper.)

8. Summary Comparison (Tantalum-Enhanced vs Conventional Titanium)

| Feature | Tantalum-enhanced implants | Typical titanium implants |

|---|---|---|

| Bone response | Bone ongrowth + potential ingrowth (osseoincorporation) | Primarily bone ongrowth (osseointegration) |

| Surface architecture | Trabecular-like porous network | Micro-roughened or coated surface |

| Vascular support | Porosity may support neovascular penetration | More limited internal vascular access |

| Remodeling behavior | Potentially improved load distribution (design-dependent) | Well established performance, design-dependent |

| Evidence base | Emerging; fewer long-term dental studies | Strong long-term clinical evidence |

9. Clinical and Biomedical Uses of Tantalum

Tantalum has been explored in multiple medical areas due to its stability and compatibility:

- Dental implants: coatings, porous midsections, or alloy systems

- Orthopedics: joint reconstruction, revision components, bone-preserving designs

- Surgical tools: corrosion-resistant and heat-tolerant applications

- Bone grafting concepts: porous granules/scaffolds encouraging cell ingrowth

- Radiation shielding: due to material density and stability in certain designs

10. Discussion

Across preclinical and early clinical findings, porous tantalum structures appear to encourage strong bone interaction, with many studies pointing to improved bone ingrowth behavior compared with conventional surfaces. Tantalum-modified surfaces have also been associated with favorable cellular responses in osteoblast and fibroblast lines, potentially improving tissue–implant interactions.

At the same time, uncertainties remain. Antibacterial effects are still debated in the literature, and the true long-term behavior of tantalum in the oral environment—especially under constant microbial challenge, pH fluctuations, occlusal loading, and peri-implant inflammation risk—requires deeper evaluation.

Overall, tantalum-enhanced dental implants may offer clinical benefits in scenarios where improved integration is critical, but definitive guidance will depend on more large-scale clinical trials and standardized outcome reporting.

11. Limitations and Barriers

Key obstacles limiting widespread use include:

- High material cost and limited supply chain flexibility

- Complex manufacturing requirements (e.g., vapor deposition, powder metallurgy, advanced additive methods)

- Limited long-term dental data, especially beyond typical follow-up windows

- Design optimization challenges, including fatigue performance and ideal porosity/geometry

- Oral-environment durability questions, including long-term surface behavior under biological exposure

- Rare hypersensitivity concerns, though uncommon, still require consideration in metal-sensitive patients

12. Conclusion

Tantalum-enhanced dental implants represent a promising direction for modern implantology due to their bone-mimicking porous structure and potential to support deeper biological integration. Early evidence suggests improvements in bone ingrowth and vascular-related healing compared with conventional systems. Despite these strengths, cost, manufacturing complexity, and limited long-term dental evidence remain major barriers.

Future progress depends on:

- well-designed clinical trials with longer follow-up

- clearer protocols for case selection

- standardized reporting of bone response and complications

- further materials research to reduce cost and improve manufacturability

References

- Rich BM, Augenbraun H. Treatment planning for the edentulous patient. J Prosthet Dent. 1991;66(6):804–806. doi:10.1016/0022-3913(91)90421-R

- Shibata Y, Tanimoto Y. A review of improved fixation methods for dental implants. Part I: Surface optimization for rapid osseointegration. J Prosthodont Res. 2015;59(1):20–33. doi:10.1016/j.jpor.2014.11.007

- Sun AR, Sun Q, Wang Y, et al. Surface modifications of titanium dental implants with strontium eucommia ulmoides to enhance osseointegration and suppress inflammation. Biomater Res. 2023;27:21. doi:10.1186/s40824-023-00361-2

- Cabrini M, Cigada A, Rondelli G, Vicentini B. Effect of different surface finishing and hydroxyapatite coatings on passive and corrosion current of Ti-6Al-4V alloy in simulated physiological solution. Biomaterials. 1997;18(11):783–787. doi:10.1016/S0142-9612(96)00205-0

- Durdu S, Usta M, Berkem AS. Bioactive coatings on Ti-6Al-4V alloy formed by plasma electrolytic oxidation. Surf Coat Technol. 2016;301:85–93. doi:10.1016/j.surfcoat.2015.07.053

- Sabetrasekh R, Tiainen H, Lyngstadaas SP, Reseland J, Haugen H. A novel ultra-porous titanium dioxide ceramic with excellent biocompatibility. J Biomater Appl. 2011;25(6):559–580. doi:10.1177/0885328209354925

- Tiainen H, Lyngstadaas SP, Ellingsen JE, Haugen HJ. Ultra-porous titanium oxide scaffold with high compressive strength. J Mater Sci Mater Med. 2010;21(10):2783–2792. doi:10.1007/s10856-010-4142-1

- Gain AK, Zhang L, Quadir MZ. Composites matching the properties of human cortical bone: design of porous titanium–zirconia (Ti–ZrO₂) nanocomposites using PMMA powders. Mater Sci Eng A. 2016;662:258–267. doi:10.1016/j.msea.2016.03.066

- de Arriba CC, Alobera Gracia MA, Coelho PG, et al. Osseoincorporation of porous tantalum trabecular-structured metal: a histologic and histomorphometric study in humans. Int J Periodontics Restorative Dent. 2018;38(6):879–885. doi:10.11607/prd.3004

- Fraser D, Funkenbusch P, Ercoli C, Meirelles L. Biomechanical analysis of the osseointegration of porous tantalum implants. J Prosthet Dent. 2020;123(5):811–820. doi:10.1016/j.prosdent.2019.09.014

- Ore A, Gerónimo D, Huaman M, et al. Uses and applications of tantalum in oral implantology: a literature review. J Indian Oral Health. 2021;1:331–335. doi:10.4103/JIOH.JIOH_18_21

- Greenwood NN, Earnshaw A. Chemistry of the Elements. 2nd ed. Oxford: Elsevier; 1997.

- Weeks ME. The discovery of the elements. VII. Columbium, tantalum, and vanadium. J Chem Educ. 1932;9:863. doi:10.1021/ed009p863

- Griffith WP, Morris PJ. Charles Hatchett FRS (1765–1847), chemist and discoverer of niobium. Notes Rec R Soc Lond. 2003;57(3):299–316.

- Wollaston WH. On the identity of columbium and tantalum. Philos Trans R Soc Lond. 1800;90:336–337.

- Kaplan RB. Open cell tantalum structures for cancellous bone implants and cell and tissue receptors. US Patent 5,282,861; 1994.

- Bencharit S, Byrd WC, Altarawneh S, et al. Development and applications of porous tantalum trabecular metal-enhanced titanium dental implants. Clin Implant Dent Relat Res. 2014;16(6):817–826. doi:10.1111/cid.12059

- Soro N, Brodie EG, Abdal-hay A, et al. Additive manufacturing of biomimetic titanium–tantalum lattices for biomedical implant applications. Mater Des. 2022;218:110688. doi:10.1016/j.matdes.2022.110688

- Soro N, Attar H, Brodie E, et al. Mechanical compatibility of additively manufactured porous Ti-25Ta alloy for load-bearing implants. J Mech Behav Biomed Mater. 2019;97:149–158. doi:10.1016/j.jmbbm.2019.05.019

- Al Deeb M, Aldosari AA, Anil S. Osseointegration of tantalum trabecular metal in titanium dental implants: histological and micro-CT study. J Funct Biomater. 2023;14(7):355. doi:10.3390/jfb14070355

- Patil N, Lee K, Goodman SB. Porous tantalum in hip and knee reconstructive surgery. J Biomed Mater Res B Appl Biomater. 2009;89(1):242–251. doi:10.1002/jbm.b.31198

- Brüggemann A, Mallmin H, Bengtsson M, Hailer NP. Safety of tantalum use in total hip arthroplasty. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 2020;102(5):368–374. doi:10.2106/JBJS.19.00366

- Wang X, Zhou K, Li Y, et al. Preparation, modification, and clinical application of porous tantalum scaffolds. Front Bioeng Biotechnol. 2023;11:1127939. doi:10.3389/fbioe.2023.1127939

- Kim YJ, Henkin J. Micro-computed tomography assessment of human alveolar bone. Clin Implant Dent Relat Res. 2015;17(2):307–313. doi:10.1111/cid.12109

- Putrantyo I, Anilbhai N, Vanjani R, De Vega B. Tantalum as a novel biomaterial for bone implants: a literature review. J Biomim Biomater Biomed Eng. 2021;52:55–65. doi:10.4028/www.scientific.net/JBBBE.52.55

- Miyazaki T, Kim HM, Kokubo T, et al. Mechanism of bonelike apatite formation on bioactive tantalum metal in simulated body fluid. Biomaterials. 2002;23(3):827–832. doi:10.1016/S0142-9612(01)00188-0

- Wauthle R, van der Stok J, Amin Yavari S, et al. Additively manufactured porous tantalum implants. Acta Biomater. 2015;14:217–225. doi:10.1016/j.actbio.2014.12.003

- Huang G, Pan ST, Qiu JX. Clinical application of porous tantalum and its new development for bone tissue engineering. Materials (Basel). 2021;14(10):2647. doi:10.3390/ma14102647